2. What works?

Examples of effective practices, policies and programs

The Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally (iYCG) focused on:

- parenting interventions and family engagement strategies strengthen children’s home environments,

- early childhood education and early intervention programs directly support children’s early learning and well-being, and

- economic and social public policies directly influence family life and the overall health and well-being of the population.

Consider... Twenty-two year old Maria lives in a small municipality in Brazil with her husband and their two-year-old son, Javier. During this pregnancy, as with her first, Marie had fortnightly prenatal visits from the Premeira Infancia Melhor (PIM) homevisitor. During these visits, Maria had an opportunity to discuss her own health and to learn more about the developmental stage of the baby she was expecting. The homevisitor encouraged her to attend the health unit regularly for prenatal assessments. With the arrival of the baby, the visits will become weekly and will focus on the health and well-being of the baby and attachment between the mother and child. The home visitor helped eased the parents’ anxiety during the first few months of Javier’s life. Her advice on nutrition, nurturing and stimulation helped Marie feel much more confident in her parenting role. Now Javier benefits from his own home visitor, who drops by weekly to visit with Maria and discuss Javier’s development. Both Maria and Javier look forward to the visits and the simple developmental toy or game that the homevisitor will leave with them. The whole family looks forward to the community events that the PIM team organizes, which include cultural activities, sports, arts and crafts, but most importantly provide families with an opportunity to build friendships and support systems. Marie and her husband are excited to show-off their new daughter at the next community get-together. Despite the economic challenges in their lives, they feel confident that they can give her and Javier a joyful childhood and a positive future.

Across the ocean in a rural village in Africa, Esther and her husband welcome their new daughter, a sister for their two-year-old son, Nelson. Esther has found this pregnancy more difficult than her first. Until recently, Esther was able to carry Nelson on her back for much of the day, but now he is constantly on the move. It is challenging and exhausting to care for a toddler while doing the daily household chores, maintaining their small garden, and making the daily walk for water. Esther knows the importance of staying healthy during pregnancy, but the nurse visits to her community are infrequent and often unscheduled. She was only able to connect with the nurse once in the past seven months. The nurse warned her to take better care of herself, to eat more nutritious food and get plenty of sleep or the baby’s health could suffer. In fact, the baby has arrived early and is underweight. Esther and her husband are anxious about her health and want to do what is best for her. Esther keeps the baby close to her in a sling, so that she can easily feed and comfort her. Nelson is having to grow up quickly, helping with simple chores and finding ways to amuse himself as his mother focuses on the new baby. Esther promises herself that when the baby is a little stronger, she and Nelson will make regular walks to the nearby village where she has extended family and friends.

- What are the significant differences in the lives of these two families?

- How have these differences impacted on the parents?

- How do you expect they will impact on the children?

Repeatedly, presenters at the Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally emphasized three essential elements of effective ECD programs and policies: nutrition, stimulation and protection from abuse.

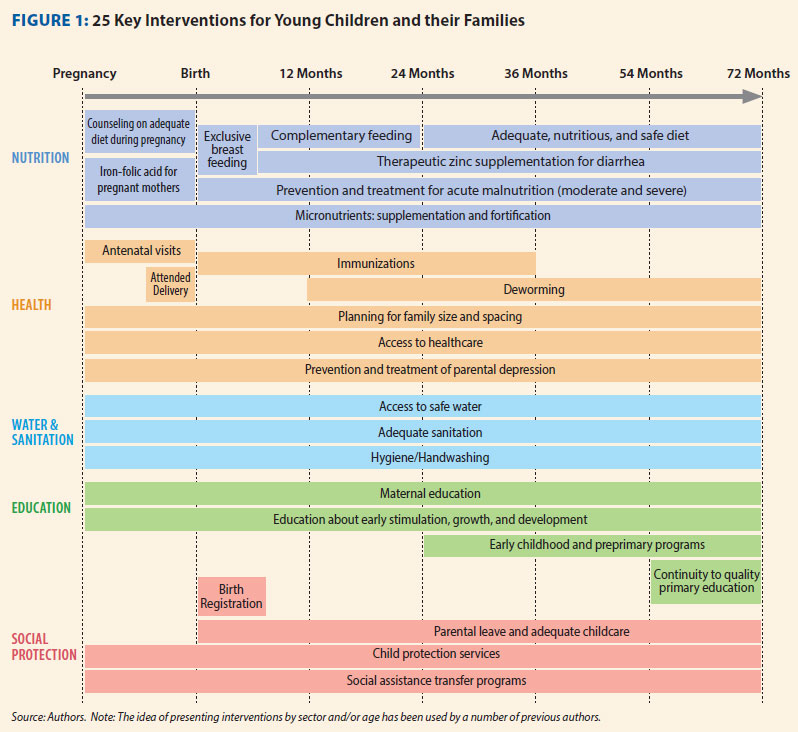

Science can help communities and governments make decisions about the right intervention, at the right developmental time. Scientists agree that there is a continuum of investments and services which need to be provided over the developmental stages of the young child – both to support parents and their children. There is also concurrence that investments and interventions must be implemented in consideration of the community and family culture and context.

At the 3rd iYCG Workshop in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Claudia Costin of the World Bank shared the chart below, to illustrate the continuous and over-lapping nature of programming needed to support healthy early development.

Click to expand in new tab

- What strikes you about this chart?

- If you had the opportunity to implement 50% all of the components on this chart in a community, how would you decide? Who would you consult with?

2.1 Parenting Intervention/Family Engagement

Home and community-based approaches that support optimal caregiving within families can maximize opportunities for young children. Family and other caregivers learn by doing. Existing community workers and home-visitors are assets in carrying out integrated programming.

Watch the interview below with Susan Walker as she elaborates on the Jamaica study.

Walker - Jamaica Study

Okay, the Jamaica Home Visiting study began in 1986 and enrolled stunted children, and at that time we were just learning that they were particularly vulnerable to poor development. And it was a trial of nutritional supplementation, as well as psychosocial stimulation. And both of those, we found out over the two years of the studies, benefitted children's' development, and the children who received both did the best. But what we then followed up the children through childhood, and the latest follow-up at age 22, and what we found was that the benefits from the supplementation weren't sustained beyond age 7, but that the benefits from stimulation, which was really around a home visiting program were committed to health workers, empowered mothers to better promote their child's development, that the benefits from that were sustained, and that over time they spread from just development and IQ to other aspects, such as educational achievement and social functioning.

- Why do you think that the benefits of stimulation outlasted the benefits of supplementation?

- If you were a policy maker, would you be tempted to cancel funding for the supplement as a cost saving measure? What should you consider in making a decision?

Watch below as Walker elaborates on the lessons from the study.

Walker - Why Effective

Well, I think there are a number of things, it's delivered by community health workers who are women from the same communities, not necessarily the same community, but similar communities as the mothers they're working with, so they're able to develop a very good relationship with the mothers. Then we also have quite a lot of training of the visitors, so that they're very clear about what they should be doing in terms of the activities to do with the mothers. But what's most important I think is not even so much the activities that they do, but how they do it. So it's very much around demonstrating with the mother and the child, letting the child explore, and then making sure that the mother is comfortable doing the activities, and over time, in a sense allowing the mother to take more and more charge of the visits, because it's about helping the mother to be more effective at responding to her child, interacting with her child, promoting her child's development. So it's very much not about the child learning in the visit per se, but that in between the visits, the mother then is encouraged to do the things that she has learned, and to interact more with her child, to speak more with her child, 'cause we put a lot of emphasis on language.

The following video includes an interview with Aisha Yousafzai, Aga Khan University and Harvard University, regarding her research utilizing a home visiting program in Pakistan. The project was the first major random control trial (RCT) in the majority world. Yousafzai explains that the components of the research program were based on ECD science. The intervention is an excellent example of an integrated approach to ECD that respects cultural context.

Yousafzai- PEDS background

This trial was designed because we found there was a real missing gap in addressing childhood interventions for the very young children from birth to two to three years of age. And the reason we found this was important was because there is so much, there is tremendous evidence from the neurosciences which tells us how we can modulate the quality of brain development in those early years and how it's good to intervene early; and we know it’s the health worker who is the person most likely to be able to support families and very young children.

And in many countries around the world like Pakistan, we also know that the risk factors that we are dealing with that cause poor development like malnutrition they are not only going to affect the physical well-being of the child but, the development of the well-being of the child.

And so, the health worker is ideally placed to integrate all of the interventions to do with better health, better development and to serve that child more holistically. So, that was the rationale for it and we began in July 2009 and the partnership that we have is with the lady health workers who are government based community health workers.

We wanted to implement a realistic intervention for them that they could integrate a child development module that complemented the health and nutrition services they already provided. So, we took the Care for Child Development module design by UNICEF and WHO, we adapted it and we’ve been training and supporting lady health workers to implement it over the last eighteen months.

So, it’s an existing nationwide program in Pakistan. They provide very basic health care to mothers and children in rural communities and in disadvantaged and remote communities throughout the country; and like many other community health workers you find in India, in Bangladesh, in Kenya, they have probably a grade ten level of education. They are from the local community they serve and they have basic health care training and a very large workload.

We give the lady health worker a baseline training of three and a half days, which is not very much and we provide them with an ECD supervisor or an ECD facilitator, who provides on the job, continue on the job training and mentorship; and the lady health worker will deliver this to a group of mothers in her own area once a month. And then she will do a follow-up home visit to that mother to see well, how the mother is getting on at home and do more individual counseling. So, the advantage of the group meetings is that the social interaction, the mothers get to see how children of different ages develop, see how different mothers work with their children, learn from each other so there is peer to peer learning and there is the social aspect, there is the… By using the groups I think we’ve created a demand in the community for early childhood development, so there is the message that’s spread; and then the home visit is the opportunity to really build the mother skills on one to one basis; and so the lady health worker is able to follow-up and she integrates that so she does that with health and nutrition.

And now we’re beginning to see that mothers see these things linking up so the discussion on the development of the child and the activities is the focus point for talking about everything to do with the child. So, that’s how it works on the intervention side.

- Why were health workers chosen to be the primary delivery agents in this study?

- Why was it important to have both individual and group sessions with mothers?

At the 4th iYCG workshop, in Hong Kong, Yousafzai’s colleague on this research project, Zulfiqar Bhutta, provided an academic presentation on the outcomes and lessons learned from their research. View the presentation below to take a deeper look into the methodology and outcomes of this study.

Bhutta - PEDS Trial

BHUTTA: Unfortunately, Aisha could not be here to present this herself so I am presenting this on her behalf and the team that undertook this work in Pakistan.

So let me start by just indicating to you how diverse and challenging Pakistan is. If you look at various measures of multi-dimensional poverty index by districts, you can get a sense that the country is not only diverse but also faces huge challenges in terms of both infant mortality and many elements that go into the estimation of MDPI. So there are parts of the country where living standards may be comparable to what you have in the West and there are others where conditions are comparable to Sub-Saharan Africa.

The importance of knowing this is that there is a fairly close relationship with not only just this distribution pattern but also health services availability and access. So, if you take the distribution of skilled birth attendance as a measure, you will find that in many parts of the country this is really quite low in terms of access, reaching only about 10 or 20 percent of the population. And you see this for a range of other dimensions such as, for example, access to children with respiratory infections, particularly pneumonia, and you find that the clustering of children who have appropriate access is largely around the areas where you have higher human development indices.

And the same with the distribution of nutrition as a risk factor for adverse outcomes. I am deliberately showing you this graphic to make the case as to why it is so important to integrate nutrition within health and developmental interventions in Pakistan, and the reason for the government moving into a program that could reach the poor and remote parts of the country.

The program that I am talking about is the Lady Health Workers Program. It was one of the first community health workers program developed in the public sector in 1994. It started off with a relatively low number of health workers which, by 2011, had reached about 100,000. If you look at the distribution of these health workers in contrast to other cadres of workers, you will see that in contrast to physicians the number has kind of plateaued over the last few years to around the 100,000 figure, and they are largely distributed in rural populations. Physicians, we have plenty, but they are mostly clustered and concentrated in urban populations.

What do these lady health workers do? They have largely a preventive and promotive role. They were principally put in place as primary care workers for family planning promotion, antenatal care provision and some commodities, health education and principally for referral of very ill children and women. They do not, in general, provide curative services beyond oral rehydration and maybe simplified antibiotic therapy for respiratory infections. Their role is primarily supportive.

The idea here was to enhance the quality of nutrition services that these public sector health workers provide, and that was largely through strengthening of both the commodity provision as well as the education part of this, particularly in the early part of infancy, and also improving the use of commodities within this program such as micorugian powders being distributed by these health workers.

There was a lot of interest expressed at the time when we conceptualized this study on also integrating some early child development interventions, and particularly those that related to the care for development package that was being developed by UNICEF and WHO in close coordination. This project, when it was conceptualized -- very few people know this -- was principally discussed between me, UNICEF and WHO in the cafeteria of WHO headquarters in Geneva and written on the back of a napkin. That is how this project came about as a two-by-two plus randomized trial.

The idea here was to look at the adaptation of the care for child development package and to look at its focus on the first 24 months of life, by and large using public sector health workers to organize the interventions to be layered on top of their regular activities. Remember this is a public sector program, so what was designed here was to integrate these activities into a public sector program.

It took us about one year and a half to get the permissions and to get the program onboard, to develop the job aides and also the tools for data collection, and a cluster randomized trial was done which principally had these lady health workers working with lady health worker supervisors.

The additional thing we put in place within this project was the ECD facilitator. These were not part of the government program; these were additional individuals who were embedded within the program who hand-held these health workers and provided some ongoing support and provision of feedback. The idea here was to work with both the mother and the child as a diet throughout the course of the project.

I am not going to go through the project in detail except to say that in terms of provision of individual counseling that the lady health workers were also encouraged as part of this project to undertake group counseling work. So the idea was to also maximize their reach by reaching a larger number of individuals in the project.

You can read the paper for the details. This was a cluster RCT, about 20 clusters in each group, a two-by-two factorial design, and all together close to around 1200 kids were followed up until 24 months of age with relatively low attrition. The overall mortality rates in the various categories are also available and are comparable with the general under-5 mortality for this district.

I am going to show you key findings. The key finding from this trial was a pretty significant and notable impact on development of outcome. This is one measure. There were several measures used in the trial. This is the Bailey score at 2 years of age. If you look at the impact estimations in the ECD exposure groups, both the ones which had ECD alone or ECD and nutrition together, you see a significant impact on cognition, language, motor behavior, and less so on social and emotional factors. This was significantly better than the enhanced nutrition intervention alone.

The effect sizes are also summarized in this paper and they were generally pretty impressive. You will see that there was no additive benefit in this two-by-two trial of adding ECD to the enhanced nutrition group in terms of developmental outcomes. That was a bit of a surprise because we expected intuitively that that group would do the best, but it did not in terms of its overall impact in comparison with the ECD group alone.

There was evidence of integrated delivery, and if you look at a range of process indicators both in terms of receipt of commodities in terms of mothers who had been provided counseling both for breast feeding and continued breast feeding and complementary feeding, overall the nutrition intervention group appeared to do well. But also the ECD group did comparably well. So there was not a clear benefit within the nutrition group alone of integrated delivery of these interventions, but all were much better than the control clusters.

The families loved it. From the qualitative data available, the families really liked the interaction with the lady health workers, both within the group one-to-one contact as well as individual visits. You could see that by the satisfaction ratings across the standardized set of measures over the course of the study.

There was not a clear impact on dietary diversity. You see at different time points 12, 18, 24 months, the diets did improve over time but there was not a huge difference between the nutrition clusters and the child development clusters in comparison with controls. That was largely because this was a rural and relatively food-insecure population where no additional food supplements were provided.

We also did not find a significant impact on stunting. There was some difference between the groups for linear growth but no significant impact on stunting.

This was a complex project and I am going to summarize in the last few slides what exactly happened here and what did the lady health workers really see in terms of determinants of their practice.

Three things - supervision made a difference, experiential learning made a difference, and there were other factors that affected their performance negatively such as their being utilized in other activities such as the polio program and their having to be absent from that area.

To conclude, there are many learnings from this project of trying to layer ECD within a public sector program. Firstly, the interruption of new interventions is not a simple thing of just walking in through the door to say do this. You have to really negotiate this with both the program people and also the health worker supervisors. And you will need to, as we did in this project, provide some embedded support as we had to do with ECD facilitators who were able to provide demonstration coaching and feedback.

Quality mattered, and it improved over time as people got better in doing this, but this required a fair amount of input and time contribution with master trainers who needed to be part of this project.

We found that mixed methods of delivery were important, and although one-to-one counseling is what lady health workers generally do, the group counseling that was tried, which is what we have done with our perinatal projects, was also extremely popular and effective in terms of reaching people.

Home visits were effective in terms of both problem-solving and observation of behavior, and it also required the development of a curriculum alongside with this project that needed to be sold and the public sector program brought onboard.

Lastly, I want to talk about [inaudible] and I will take just a minute for this. Can I go to the national program today and, on the basis of this large district-based project, say do this? The answer is no, because we need to step back and see to a certain extent what are the questions that the program people will ask and have asked.

The first is really the time commitment. These are public sector primary care workers whose principal charge is to reduce mortality and to provide child survival interventions. Therefore, anything that you do has to have a time component clearly attributed to their tasks.

Secondly, the questions around what would be the impact on their core functions. As you will note from the paper, there was no reduction in mortality. If anything, there were some counter-intuitive trends which do suggest that as we scale up these programs we have got to make sure that the core functions of these public sector workers, which are largely in high mortality areas, to make sure that life-saving interventions are delivered and are not compromised. I am pretty confident they would not be, but we need to prove that and show that to the program people as these programs are scaled up.

Costs are an issue. We had to put people in place, extra people, and provide support. As you take this forward, this is not an insignificant part of their activities.

Lastly, most importantly in my opinion -- and I am reflecting on the first presentation of the day -- it is extremely important to think out of the box and out of the health sector. Irrespective of what is the service delivery pattern, whether it is home visits or group counseling, we did not see an impact on nutrition because these health workers had no link with the nutrition-sensitive sectors. They could not do anything for food insecurity; they could not do anything for wash, they could not do anything for agriculture or social protection because they are not linked to those programs.

Therefore, a heavy investment in this has got to take into account that maybe that is a role where health workers and non-health workers have to work in tandem. Or perhaps we need to find a modality of delivery which brings a multisectoral worker or intersectoral worker together at the district level.

Thank you very much for your attention.

2.2 Early Childhood Education and Early Childhood Interventions

Child care arrangements can be nurturing and educational. The best child care arrangements are not those that have the most expensive toys and equipment, but those that are most responsive to the developmental needs of the children, including reinforcing the value of play. ECD programming also increases the opportunities to identify risks, delays and disabilities and intervene early to maximize all children’s developmental potential and quality of life.

Child care arrangements can be nurturing and educational. The best child care arrangements are not those that have the most expensive toys and equipment, but those that are most responsive to the developmental needs of the children, including reinforcing the value of play. ECD programming also increases the opportunities to identify risks, delays and disabilities and intervene early to maximize all children’s developmental potential and quality of life.

At the Brazil workshop, Claudia Costin discussed early childhood centres.

Costin - Early childhood centres

MS. COSTIN: Good morning. It is indeed a great honor to be here. I have been working with Maria Cecilia Souto Vidigal for many years now, a great partner, and does a lot in the city of Rio de Janeiro where we could develop a very interesting and innovative model of early childhood education -- and I will talk a little later on that -- and build more than 200 early childhood centers in 4-1/2 years, based on this new model.

I have to say that, yes, my emphasis is on education but it is key to our strategy to be able to work together -- education, health and social protection. I was very happy when I joined the World Bank on July 1st to see that this is also part of the strategy of the World Bank, to work together, the three sectors, because you cannot ensure a healthy childhood and a future healthy adult without putting the three areas to cooperate, which is not easy. Whoever has worked with policymaking knows it is very difficult to put the three secretariats to work together in governments, or the three ministries, depending on where you are, at what level you are. But it is central to the effort of early childhood development to put the three areas working together.

I would like to say that the Forum on Investing in Young Children globally is very important, and it has a key role when it comes to gathering information from many partners. Yesterday I was able to talk to the Dean of UCLA about information we need to make good recommendations to governments and to policymakers. And we at the World Bank are very happy to be one of the sponsors of the forum and to have helped in the past, previous to my arriving here, the core group, with the organization of the first two forum meetings in D.C. and in Delhi. We look forward to helping in Ethiopia. I am not going there for that specific reason now, but we are looking forward to helping them. We need to see the children. Children should be at the center of everything we do, so investing in young children is one of the smartest investments a country can make. The first years of life, as everybody here knows, are crucial to healthy development, and that is just a start. Children need regular mental, social, emotional and physical stimulation along with healthcare and proper nutrition to keep their development on track.

But also, we have to look carefully at three areas -- quality preschool programs. It is not enough to enroll every child in preschool programs. In Brazil, I can say we have the goal to ensure in 2016 that every child goes to early childhood program. But that is not enough. It has to be a good quality program. There are studies that show that bad quality preschool programs are even detrimental to the child development. Even though this is important, in low-income countries, parents don't always have this opportunity either because the private sector offers pricey alternatives and the government has not invested in preschool programs, or because parents don't understand the importance or the benefits of such programs.

There is a range of options when it comes to preschool, from low-cost community models when you don't have the government investing in it that meet just a few hours a day, to full-day, more expensive programs, sometimes within the walls of primary schools, which is not ideal but is better than nothing, especially if quality is high in these programs. As I mentioned, not all parents are aware and not always government invests, so too few children benefit from early childhood development service. Less than 50 percent of the three to six-year old children in developing countries are engaged in any form of pre-primary education. Only .1 percent to 2 percent of the GNP in many developing countries is spent on preschool education. Our impression is that governments are not aware of the importance of these investments, either. As is well known here, especially among the health professionals, one-fourth of the children under age five worldwide are physically stunted. That means 162 million children, with 56 percent of them living in Asia, and 36 percent in Africa. This has to be changed urgently.

How can countries devise low cost if they don't have the resources, approaches to offering early childhood services sustainably, because it is not consistent to have an effort and then stop, and the stop and go approach won't help young children.

A key question is to expand ECD coverage at low enough cost so that it is affordable and the government can continue to invest. I am not saying that all countries have to take the low-cost approach. For countries like Brazil where important investment has already been made, it is important to continue on the route of quality, but we have to ensure ECD education programs for all, not just for the ones that have already invested, and look at quality at the same time.

The World Bank works with countries with multiple entry points to investing in young children. Our portfolio includes investments across health, nutrition, social protection and education practices. We are organized now by practices, and the three practices are working together to make a big offer for governments on loans, grants and policy advice so as to ensure that these areas are covered.

On child nutrition, including food fortification, community nutrition and security, on maternal and child health including promotion of breast feeding, prenatal care, newborn health, immunizations and child survival. Early childhood care and education, including pre-primary education, school readiness and parenting education. It is important when we talk about school readiness to understand that preschool education is important not only to prepare for basic education, but it is, in some sense, an end in itself. If you can have happy children being developed, it's not important just because of education, the future education. It's important at the present. It's important to have healthy children and for them to be happy while they are children. It is related to a basic child right.

Family support and inclusion including social assistance, safety net and conditional cash transfers. I think this country has been an example for the work with the Bolsa Familia. In Rio de Janeiro, we have complemented Bolsa Familia cash transfers, giving additional money with conditionality related to early childhood programs including attendance at preschool, parents participating in parent crashes and teacher meetings every two months. The school for parents is a condition. Or, if the parents don't want crashes, an alternative Saturday program so that kids can be at least monitored from a health perspective and social protection perspective.

Central to all this, as I mentioned before, is integrated, multi-sector ECD projects and evaluations including integrated health, nutrition and education interventions, impact evaluations of ECD and support for governments to improve ECD policies.

Just to give you some numbers -- the numbers are not as important as the trend -- to see that ECD is at the center of the strategy of the World Bank Learning for All education strategy. It starts with invest early, so it is in our education strategy. In the last 14 years, we have invested nearly $4 billion in ECD through multi-sectorial projects. But if you notice what happened in fiscal year 2011, you can see the upward trend in investment. When I talk about investment, it's loan grants and analytical work, studying what matters. It is central to the World Bank the idea of assessing experiments so as to see if there is evidence to scale up and to recommend governments invest. Those are some examples of our analytical work that we have done lately.

We have a guide for policymakers making recommendations for early childhood. As Claude mentioned when she was talking about health, our initiative starts with pregnancy, not when the child is born. If the mother has a non-healthy pregnancy, it can have a bad outcome for the child. So I won't go into details of the strategy due to my limited time, but we cover pregnancy, birth, the first 12 months, the first 24 months on nutrition, health, water and sanitation. Water and sanitation is central to child health and also brain development.

And when we talk about education, it is not only the child's education but maternal education as well, ensuring the parents will know how to care, to build healthy bonds with the child, and also to stimulate the brain and read to the child. Just a quick example from Rio that was centered to our school for parents in Rio, three Saturdays a month we have a library of baby books that can be lent to parents to bring home in vulnerable areas, and this is for the Bolsa Familia children. They have baby books at home, and we give them baby books not only from the library but for them to build their own library. These are just some examples on education including certainly crashes and preschool. And social protection on the cash transfer system and other modalities.

While there has been an uptake in the last decade for early childhood investment, resources for ECD remain low in many countries. There is not only good news. This is in part because policies and programs related to early childhood development are complex and managed by multiple ministries. I was talking two days ago to Constanza on the difficulties of putting the ministries that are important to early childhood to work together. Sometimes the ministers agree, but in the bureaucracies of each ministry or each secretariat, depending on the level, there is resistance to working together. This is part of our problem and this has to be central to policy recommendations.

In addition to the guide to policymakers that we prepared, we just launched an e-learning course on ECD. We want to compete. I was just joking with IDB who also has a very good e-learning course. We just launched it in October. I would strongly recommend it; it is open to everyone. It is not translated in Portuguese, but it is translated in Chinese. You can choose either English or Chinese.

The course consists of three interactive web-based modules with 15 topics of total learning time of approximately 4 to 5 hours. Important modules like why invest in early childhood, what matters for early childhood development, and how should early childhood interventions be implemented.

On impact evaluation, let me very quickly talk about it. I am a policymaker. I've been a policymaker all my life working for governments, and sometimes we wonder why institutions like the World Bank and others invest so much in analytical work, including impact evaluation, as if it were losing resources, not investing directly into action. But how can we know what matters and what does not? What brings good outcomes and what does not?

Impact evaluations done by the World Bank or by partners are very important. This is the example of the impact evaluation on investing in early childhood in Mozambique. Sofi is here; she has worked for years -- she is the crème de la crème from the World Bank in early childhood. Please approach her at the break and she can provide further details on what we have done in early childhood in Mozambique and the lessons learned, and she speaks Portuguese with a Mozambiquan accent.

The Mozambique impact evaluation -- just to give you one example -- to test the effectiveness of low-cost preschool programs on children's enrollment in and readiness for primary school. We supported this study of an early childhood development preschool program run by Save the Children. The evaluation showed that children enrolled in preschool were better prepared for the demands of schooling than children who did not attend preschool, and that they were more likely to start primary school at the age of six. Based on these results, the Ministry of Education of Mozambique has begun to work to expand the community-based preschool model to reach 80,000 kids in its third year. World Bank-supported researchers are working right alongside the government to evaluate the scale-up.

I am going to finish because I don't time to explain everything. I'll talk about my results from the impact evaluation in Brazil on the Rio de Janeiro daycare centers program. It was research done by David Evans and Pedro Linto from the World Bank targeting 0 to 3, coming from disadvantaged households. The program was based on full-time daycare. In Rio, we had this option of full-time daycare with a program that has even a curriculum for early years in specialized centers with teachers. We don't take 0 to 3, but 6 months to 5 years old are in these centers because we don't want to have children in centers and harm breast feeding. But we have a school for parents attached to it. Specific instructional toys and material for children, involvement by parents to foster good parenting practices.

In total now we have approximately 400 daycare centers in Rio. Still, every new daycare center that we build, additional parents want to enroll their children. We always have parents that want to register their children but cannot, so we decided to do an affirmative action, which means that parents from Bolsa Familia have absolute priority. That was a tough discussion because parents were saying, well, but parents that work versus parents that don't work. It doesn't matter. We have teen-age girls that need to go back to school and they won't find jobs if they have to take care of the children. It is the parents' choice; it is not mandatory. If they prefer to stay with their children or have a grandmother or grandfather who wants to stay with the children, they can go to the Saturday program and the school for parents.

Among the children from Bolsa Familia, there is a priority for children with disabilities, and they are not separated from the others. We have children with disabilities together with the other children, but with just additional support when needed.

So the evaluation is going on. The results so far are being very consistent and interesting. But I am eager to see the long-term assessment and evaluation of the results of such a huge and important investment.

I just want to say one final word, which is that we need to level the playing field, and early childhood development is a wonderful strategy, and yes, we are committed to change the world starting at the very early stage with the small children.

Thank you very much.

Below, Jody Heymann, University of California, Los Angeles, discusses the importance of access to quality care and the variations in the nature of quality care according to geopolitical and cultural differences.

Heymann - Early Childhood Education and Interventions

When we think broadly about what children need access to, it’s essential to get quality care giving time with adults throughout these early years. So who are those adults? That’s going to be a combination of two things. First, enough time with their parents. That’s about parental leave policies. And the second is, enough time with other quality adult caregivers. That’s really about how affordable and accessible we make early childhood care and education. There are wonderful models across different countries, different income levels about how to provide this care. It is feasible to do at scale, regardless of the country’s income level.

So in Scandinavia the early childhood care that’s at scale might look like a centre with full time professional caregivers and guaranteed access. In Quebec it might look like a disseminated model but where there’s a guaranteed, affordable fee. And in Malawi it might look like training community providers to provide it in their home or in small care settings in villages but with adequate resources for stimulation of children and for activities that really help their cognitive development and their social and emotional development.

- Heymann makes the point that ECD programing varies across cultural, economic and geographic lines. What types of programs are available in your community?

- Do families receive the information and services they need to support their children’s development?

Program developers seek ways to meet the needs of both young children and their parents, thereby strengthening the family unit and improving family outcomes. Once such program is Kidogo, a social enterprise initiative operating in Africa which strives to improve access to high-quality, affordable Early Childhood Care and Education to families living in poverty. To learn more about their innovative “hub and spoke” model designed to “unlock the potential of young children and transform the trajectory of their family’s lives” visit the website below.

- What might a "hub and spoke" model look like in your community?

The recently released 2016 Lancet Early Childhood Development Series contains a wealth of the most current scientific information on early childhood development, including meta analyses compiled through collaboration between the leading experts in ECD. The article “Nurturing Care: promoting early childhood development,” (Britta et al, Vol 389, No 10064) summarizes existing research into out-of-home care in the context of Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs). Take note of the chart that summarizes the current evidence-based interventions “for improving child development, nutrition and growth, mortality, disability, and morbidity in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), based on high-quality systematic review evidence...”:

- What stood out for you most in this very comprehensive article?

- What strikes you about the information on the Summary of Effective Interventions chart?

- Which interventions are you interested in learning more about?

You may have noticed that some of the interventions which have multiple positive effects are not programs working directly with parents, but are in fact social policies, such as conditional cash transfers. The section below will look more closely at the potential impact of social policies on whole populations.

2.3 Economic and Social Public Policies

Jody Heymann illustrates this through examples in her presentation to the 5th iYCG workshop in Ethiopia in 2015.

Heymann – Importance of Social Policies

HEYMANN: Thank you to the Ethiopian Academy of Sciences for hosting this for your remarkable work and for bringing us all together to really solve these problems together. It’s a joy to be here with you all this morning. We heard about the truly remarkable efforts being done here in Ethiopia, we also heard one of the breakouts about Colombia, and yesterday we heard many individual country success stories and challenges.

What I’m going to talk about I hope is complimentary to that, which is whether we can at the same time as learning in depth at a national level see what’s happening at a global level, and there are a couple reasons for doing that. One is it allows us to advocate better. Advocate better for resources, advocate better for change, we can look comparatively. And the second is the kind of data that it generates when we can look at policies in 193 countries and outcomes for families in all these countries, allows us to figure out what works in another way.

We need to look in depth inside countries but looking across countries can give us some really good insights too. But before I dive into the slides I do want to talk a minute about two people which maybe will help give a sense as to why policies matter as well as programs that are targeting kids directly, because I’ll be speaking mainly about the policies that help parents and families invest in their kids.

So one is a woman I met in Honduras. She was working seven day weeks, often sixteen hour shifts, sometimes 20 hour shifts. She had a little child she was raising on her own, and the question was how to do it. Now, if we had more time and in the break I can tell you more about her story because she was really a remarkable parent, but I hope that just that snippet gives you a sense that unless we addressed her working conditions it really wouldn’t matter how good the programs were, and frankly parenting skills, as important as they are, as crucial as they are, were the least of her issues. She didn’t have time to be with her child, and she was barely awake when she was with her child. I visited her shortly after this wood house on stilts she lived in had burned down because after a mandatory 20 hour shift she was so tired she went to bed, the candle was still burning, flipped over and set the place on fire.

Another was a man, because I don’t want us to forget dads. Louise when I met him was caring for his son. Super rare to see a dad home in this neighborhood with a 10 month old in the middle of the day at 10 AM. But his son had gotten sick. We talk a lot about maternity leave, we don’t talk very much about paternity leave, and we talk even less about whether parents will lose their jobs if they care for their kids. But as in many countries if he didn’t go to the hospital and his wife didn’t there would be nobody there to feed the child during the day. They were part of the care system.

And he and his wife alternated but he lost his job when he was caring for this child who by the way was in the hospital with pneumonia, having gotten it when the mom had to stop breastfeeding because she had to return to work early with no paid maternity leave. So each of these are real examples, sadly common examples, where what the parents could do was dramatically shaped by the policy environment they lived in.

So the forum looks across areas as people in the forum know, health, nutrition, education, social protection. I’m really going to talk about what are the social conditions that allow parents to invest in this, basically policies that provide parents with time to care for infants, to care for other young children, and to provide them with adequate income, including working parents who are working for their income, but how do laws and policies shape that. And then I’ll end with some of the direct investments that governments make and what we know about it.

I’ll just step back for a minute and say the World Policy Center which I direct where this data comes from, we also direct this data to outcomes. So I’m going to show you the maps of where policies are, but we’re able to look both globally and at individual country data to see how the policies change health outcomes for kids, health outcomes for parents, economic outcomes, et cetera.

So let’s start with time. So many people who are here I know are investing their energy, their resources, and the kind of care parents give their children of course to give the children the kind of quality care that these programs help support them in doing, parents have to have time with their kids in the first place. There’s really good data that it matters.

I’ll just cite one fact from this as to why some of the policies I’m going to show you count. If you increase paid maternity leave by ten full weeks you can lower neonatal mortality by ten percent. It’s a very substantial impact. That’s after taking into account what countries invest in healthcare services. That’s after thinking about sanitation and public health measures. On top of that it has a very substantial effect.

So how are we doing in the world? So it looks like for some reason these maps are not coming through. So it’s on a Mac as opposed to, should I give it to you on an IBM because these are definitely on the slides I sent you. Adaptable, great host team evidently had an IBM yesterday but they had to swap it out today for technical problems and now we’re swapping back, so thank you for your patience.

So paid maternity leave, I hope those of you even in the back who like sitting in the back row like I often do can see which countries have paid maternity leave, the red ones don’t. It’s not much of a geography test I’m afraid. So who is it? 187 countries have it, the ones who don’t, Papa New Guinea, Surinam, a few small South Pacific Island states, and the United States of America, which we hope will not be red for long.

But the good news about this map is actually the world is very far when it comes to paid maternity leave. There’s a lot of diversity in how long it is, and I think one of the things we can learn from monitoring the data is the different benefits of how long. We can also start to understand the impact for example of having prior to the birth leave as Ethiopia and a number of countries but not all countries do.

The color of the map looks really different when it comes to dads. So you might notice that all of a sudden we have a map that’s overwhelmingly red. That’s because most of the world does not do anything for paid paternity leave, we should worry about this. Paid paternity leave the data is really good, this is when dads set the tone as to where they’re going to be involved long-term.

When countries give paid paternity leave they have a longer involvement years after the paid paternity leave, there are lower rates of maternal depression. Kids do better, but only about half of countries offer it, and of those half only a quarter offer more than three weeks. There was global agreement on maternity leave, that’s probably why we have such a better map. We need that same kind of global agreement for dads.

There is by the way a glowing movement among men’s’ organizations working through this in Brazil and South Africa and elsewhere, and we should think about how they intersect with the work we’re doing on zero to five. So this is about breastfeeding breaks.

I think we’re all familiar with the fact that breastfeeding lowers mortality three to fivefold, it’s one of the most powerful interventions we have, but it’s far from as simple as just telling moms breastfeed because it’s good for your babies, most women now work in the informal economy, and when you ask them do they want to breastfeed overwhelmingly they say yes, including those who are in the paid labor force, but when they get to work they stop.

So the question is how easy do we make it to continue. The good news is about three quarters of the world takes that first step of allowing breastfeeding breaks. And I say first step, because if your place of employment is an hour away from where you live, if you have no refrigeration, if your baby is far away, that will not get the job done, but it is an important first step.

There are 50 countries around the world that neither have breastfeeding breaks nor have maternity leave for six months. So what does that mean? That means that we’re recommending as healthcare professionals, and the World Healthcare Organization is recommending six months of exclusive breastfeeding, and it’s just not possible.

Care obviously goes long beyond those years though, beyond the first year of life. Time investments matter. We did in depth studies, I’m just going to cite a few. In Botswana, Mexico, and Vietnam you can see the numbers there, 49 percent, 42 percent, 49 percent reported having serious trouble caring for children when they were sick. That meant they left them home alone when they were sick, they left them in the care of other sick children. This is a very large problem that we know paid sick days if you won’t lose your job make a big difference.

This is particularly important for young children. Older children with common illnesses may do okay without parental care, but the very young don’t. This is what the map looks like. If you look at the world you can see we’ve spent a lot of time talking about maternity leave, but just as we had a gap talking about dads it’s as if we think the parents care for the baby during the leave and then the baby just cares for him or herself afterwards. Unfortunately that’s not the case.

So only 60 countries, about a third of the world, gives paid leave to care for your sick child to both moms and dads. That’s a very small amount. A few more give it just to moms. Pretty problematic in terms of gender equity. Most of the world doesn’t give it to anyone. About 15 countries give unpaid leave.

It was raised earlier that obviously parents have to be healthy themselves as well. We’ve come further in terms of giving parents who are working leave to care for their own health. We should care about that for their health, but it also tells a happy story that this is in fact possible. When it comes to paid sick leave for the adults, nine out of ten countries do this. Overwhelmingly the world does it, I apologize that the United States still looks red. To anyone here from India many Indian states do give it, it’s just not given across the whole country. But the fact that we’ve achieved it for working adults, we should be able to achieve it for their young children too.

Now, clearly we know income matters, and there are fundamental investments, whether it’s in nutrition, whether it’s in books, whether it’s in other school supplies the parents need to be able to make, and a core part is where they’re getting their income floor for this form.

I hope we can start talking about the minimum wage as a way of investing in young children globally. If you look at how most parents exit poverty they exit it by their work. Their biggest source of income overwhelmingly is their work. In terms of the informal economy, even though it’s not directly covered by the minimum wage, the good news is most of the world has started to have a minimum wage, but while we talk about global poverty levels we have yet to address the fact that in a third of countries if you’re a working adult earning the minimum wage that will not bring you and your child above two dollars per person per day. So if we want to reach that we have to be able to let people work their way out.

So fortunately we’re no longer in a global recession or at least not in the moment. But the unemployment safety net has a huge impact on children. The most important thing I would say is that everything that’s yellow or orange here are areas where in the informal economy where we know many of the poorest families are there is no coverage during periods of unemployment for you, there’s not an effective safety net. That’s because the mechanism is severance pay, it’s a pension you have to contribute to and you’re not allowed to contribute if you’re in the informal economy. The blue countries are the ones that have solved this. But we should be thinking about that.

And I’ll skip ahead because of time and just say we also have to think about intergenerational transfers. I’m sure many are familiar with some of the studies from southern Africa showing when you give pensions there are direct benefits to young girls in families, but we see these inter-generational transfers in high income countries as well as low income countries, so we should wonder what the pension maps look like.

If you’re a parent and your own parents are living in poverty you are going to need to support them. But likewise if you’re a grandparent and you have income available and your grandchildren are in need you’re more likely to support them. So these really are not competing investments, they’re complimentary investments.

So the one direct investment I want to talk about is tuition free pre-primary school. So we were struck, we went around to find out how many countries around the world do give tuition free pre-primary, and 43 percent, nearly half, give at least one year. That was better than we thought we’d find. That includes five percent of low income countries. It’s a small number but they’re showing it’s feasible.

And it includes the majority of high income and close to a majority of middle income. We should be starting to track this. We should also look at the outcomes and how it matters. This is the map of tuition free primary. So all blue, nearly the whole world provide it. Just imagine going backwards, that that pre-primary map when we next meet in five years looked all blue too. So what’s the impact of this?

The impact, and for those sort of quants in the room I’ll explain that this is a hierarchical multi-level model that links it to household data. For those non-quants I would just say what this does is it looks at the policies and say did it change outcomes in 90 countries, and the answer is it did. It lowers infant mortality when you provide free primary, when those moms who at a chance at free primary become parents, then you have lower mortality rates.

So I’m going to close for a minute by talking about critical data gaps and then turning it over to you all. There’s much more we should know. One thing we don’t have at all is data on the direct investments in zero to three. I showed you free tuition for pre-primary school, but all of the fantastic programs that people have been talking about here for the past two days and when we met in Brazil, we should be able to map those around the world.

We should be able to help countries see what neighbors are doing, we should be able to link those to outcomes. That’s feasible, but that data has not yet been collected globally. But we should also monitor progress, because it’s only by showing every year when countries are starting to move towards better supports for families investing in their own kids that we can reward the policy makers and the leaders who are doing it and help press those who have yet to make change to make it. Thank you very much.

Employment policies and practices shape family life. Heymann outlines several examples in the interview below.

Heymann - Parenting Intervention

There is so much that countries can do that’s transformative for parents and for young children. So just to give a few examples: Many women want to breastfeed, not all women can breastfeed. So we know that the major World Health Organization and other agencies concerned with all of our health recommend that mothers breastfeed exclusively for six months. But if you’re at your job and they do not allow you to take a break to breastfeed, you won’t be able to no matter how much you want to. If your family depends on your income, you need that job. So what can countries do and what in fact, are two thirds of countries around the world doing? They’re guaranteeing leave for mothers to breastfeed. The other one third could step up to the plate and start to do this. Any country that can afford to give breaks for lunch for an adult can give that break for a mother so that she can feed her young child. That’s a simple example. Another incredibly important area is parental leave. So when there is a new born child, do parents have time with that child? We know those first weeks and months are particularly critical and the care needs to be one on one or one adult on two children and the way for that to be accomplished is for parents to be able to take that leave. 187 countries; nearly every country gives paid maternity leave. The number giving leave for new dads is only about half as much; we have much more progress to make there. But also there’s still a few countries that don’t including the United States which could afford to.

I think one of the attitudes we have to beware of is when we assume that if parents are not providing enough care to 0-5 year olds it’s either because they don’t want to or they don’t care enough to. So often for families the reasons that they’re not providing care is they have no choice. And we know that from interview studies we’ve done of families around the world. So I’ll just give some examples of a 19 year old mother who was single mother; her husband had died, working 15 hour shifts in a factory 7 days a week with an 18 month old child. It doesn’t help to tell that person, spend more time with your child. She desperately wanted to spend more time with her child. What helps is to make sure she has; can earn a livable income with decent hours that allow her to spend that time. I think there are just so many examples of this. A second area where are; where broadly held misconceptions sometimes I think get in the way, is how much we forget about fathers’ roles. Fathers are so critically important in children’s lives, just as mothers are. We need our national policies to reflect that. Part of not only gender equality, but children doing well, is giving fathers equal leave, making sure they have sufficient time when they’re new born children, when children are sick. That should involve men and women.

In her full presentation in Ethiopia, Heymann made the point that “if you increase paid maternity leave by ten full weeks you can lower neonatal mortality by ten per cent. It’s a very substantial impact.” Most but not all countries have implemented paid maternity leaves of some kind.

- Consider why governments might resist implementing meaningful periods of maternity leave.

- What information would be helpful in overcoming that resistance?

Summary

Poverty and inequality are among the most significant threats to healthy ECD. Social policies that address poverty and transfer greater income to families living in poverty can have immediate impact on the well-being of children, as well as long-term benefits for the family. Income transfers can reduce inequality and poverty.

In this section we have explored what works to support positive early childhood developments. Effective approaches include:

- Services that work directly with parents, drawing on emerging science and utilizing trusted local service providers.

- Child care services that support both the development of children and strengthen the capacity of the family.

- Social and economic policies which by empowering parents can make a dramatic difference in the lives of children and families.

Test your understanding with this review. Click on the arrow to the bottom right to begin.

Test your understanding with this review. Click on the arrow to the bottom right to begin.