1. Investing in Young Children

Why is it important to invest in young children?

The Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally (iYCG) focused on:

- overwhelming scientific evidence that reveals how potent early life experiences are in directing individual and societal development and prosperity,

- findings from economic analyses that repeatedly point to the high return on investments in ECD, and

- capacity for ECD programs and resources to remove barriers to opportunities and reduce inequities for young children and their families.

- What are the potential benefits of this approach for Janel?

- What about for Ardel?

- Why would the local government invest in a program such as this?

The Long Reach of Early Childhood makes the case for investing in young children through the voices of experts, community people and children from around the world.

- What resonates for you in this video?

- Why might ECD be key to the future prosperity of nations?

- Why is support for maternal and child health emphasized as a priority by several of the experts interviewed?

If the future of the planet matters, early childhood matters a lot. Early childhood sets the foundation for lifelong learning, behavior and health. What transpires in the first few years of life matters to each individual child and to society. Today’s youngest citizens will determine how the human species copes with the challenges we face globally.

At the iYCG workshop, The Cost of Inaction, held in Washington, DC in 2014, Peter Singer of Grand Challenges, Canada argued that the critical importance of investing in ECD is lost in translation between research and practice. He maintained that effectively supporting ECD worldwide is a complex but crucial challenge – a grand challenge – and that "not getting the early years right leads to serious economic, social and health consequences."

Singer - Part 1

Thank you very much. I am also a FOZ. It is a friend of Zulfi. It is not why I am here. Actually, when I am done, I may not be a FOZ anymore. I just want to say how humbling it is to be here with all of you in terms of the awesome work that you are all doing. I think this forum is an amazing idea and hats-off to Kimber and to Patrick and to your whole staff who developed this. Thank you very much for this invitation to address this very distinguished group.

Your work on investing in young children really does have the potential to change the world. As an IOM member it is really a privilege for me to be able to contribute in this small way to your incredibly important work. I should say right up front that I don’t consider myself a technical expert in early child development. Having the privilege to lead an organization that has invested so far 28 million dollars into this field and we are planning to do much more on this challenge, I am very interested in making sure your initiative succeeds. You can see some of those 28 million dollars of investments in a framework I will come back to on the handout that I have given which is up on this slide.

I also want to acknowledge the brilliant leadership on this challenge of my talented colleague, Karlee Silver and also Dominique McMahon who have been working very hard on behalf of Grand Challenges to integrate into your work. I just want to acknowledge them.

Having started off that way, today actually I don’t want to focus on success. Where I want to focus is on the issue of failure. The reason I want to do that is I think acknowledging failure is likely the most central element in an ultimate success. At the beginning of a series of workshops what I actually want to do is focus on what I see is potentially a collective failure of our whole community. I call it lost in translation. I will describe what that is in a moment.

I want to say upfront when I talk about failure, I see it as a really good thing. My favorite characterization is that Disney film Meet the Robinsons, where the family is around the dinner table one night, and the father says to the son, “Let’s congratulate Lewis on his brilliant failure.” It is exactly in that sense that I think we are failing in a particular way that I will specify.

I also want to be clear upfront that I think this field is full of amazing people doing amazing work. So when I talk about failure, it is in no way a critique of these individual efforts that have been awesome, but rather an acknowledgment that we are not where we want to be in terms of results in a particular way that I will describe in a moment.

My only reason for focusing on failure is because I think we are capable of a huge win in child development. I don’t think we are going to get there unless we acknowledge where we are at, where we are doing well and where we need to do better.

Where do I think we have failed? I think we have failed to translate the emerging evidence in early child development that is being so interestingly synthesized by this forum. The science, the empirical evidence from clinical studies, the economics into commensurate attention on the part of policymakers and that is what I mean by lost in translation.

The scope of the child development challenge, which we call Saving Brains at Grand Challenges Canada, only to put it apposition to this incredible emphasis on saving lives is not reflected in my view -– and I will try and prove this -– in the global policies and accountability frameworks that are going to guide what plays out over the next 15 to 20 years. My hypothesis is that ECD is lost in translation.

Let’s start with what the evidence tells us on the one hand. On the hand what is at stake, simply put -– again, keep in mind, I am not a technical expert -– as I synthesize the evidence, it seems to me that child development is one of the world’s grandest challenges. It really is in its scope, in its scale and in its impact. Not getting the early years right, as many of you have actually shown in your work, leads to lower wages and GDP, so it is a serious issue of economics for countries, higher rates of criminality and conflict so it is a serious issue of the social fabric and also higher rates of non-communicable disease and depression.

I would like to say that even if you didn’t care about the health outcomes of non-communicable disease and depression, the economic and social outcomes of child development are extraordinarily dire. If we don’t pay attention to child development what this in effect means is we are killing entrepreneurs, creating criminals and promulgating sick and depressed populations. You can’t really have a challenge where there is more at stake than that I don’t think.

This inattention to child development in policies and programs is tearing apart the socioeconomic fabric of countries. Not paying attention to early child development can lock countries into poverty, while focusing on it represents a potential exit strategy from poverty.

Here, let me just remind you what people hate about foreign aid. What people hate about foreign aid is that they don’t see an end to it. They just see it as one charitable contribution after another, after another, after another. Here, with child development and growing human capital, you have actually got potentially an exit strategy from that thing that people hate about foreign aid.

This is a bit of an overstatement, why bother focusing on primary and secondary education if you are already walking up the down escalator. You are already going the wrong way on the treadmill by the time a child gets to school if you don’t pay attention to early child development. Child development is the bridge between maternal and child survival in primary education.

In some ways, it is actually the first skills training program that a country can have to build its workforce. In short, child development, really, I think is one of the grandest challenges of our time. There is an incredibly compelling case on the challenge of child development. That is the evidence that you are synthesizing here.

On the other hand, let’s have a look at how this incredibly compelling case and this compelling global challenge have been translated into global frameworks for action. For starters, let’s have a look here. This is just a quick snapshot of the post-2015 process kind of where it is now, the focus areas of the open working group, which is the successor to the MDGs and will guide global action for the next 15 years.

Again, let me acknowledge, I know many people in the room have been working hard to get child development into this framework. In fact, as you can see from this slide, child development is in this framework. If you go under each of these headings, and if you click on the agriculture and nutrition heading and you go down one level, it does explicitly mention stunting. If you go to the education bullet, it does explicitly mention early child education.

On the health bullet, it mentions a number of things closely related to child development, like sanitation and vaccines. Under peaceful and nonviolent societies at the end, if you click down at explicitly references, protection of children against violence, it is all there. I want to argue that child development is really sliced and diced in this open working group framework. It is not viewed in any holistic manner. It is not seen for the grand challenge that it truly is.

Now, you might say that the world has many problems, energy, poverty, joblessness, environmental challenges, and that is certainly true. In the face of these, it is difficult for child development to emerge as signal amidst all of that noise. Okay, to test that contention, let’s have a look at the MMCH Specific Frameworks for Accountability.

Here is a picture of the Countdown Framework, and Zulfi is very much behind this. He has actually done amazing work, and I hope I still will be a FOZ when I am done here. He is putting his fingers down. This slide I actually borrowed from Tarun Dua who I think is here in the room.

When you look at this Countdown framework, there is no question that child development is here, but it is implicit. One of the main outcome indicators here is stunting, which is related to child development, but I would argue may be more towards the biological/nutrition set of risk factors. I think we could argue about that. Also, many of the same health interventions that are tracked in the Countdown Framework affect both survival and health and development. So there is no question that it is here. I think it is implicit.

Does this framework reflect the social and economic significance of child development? I would argue, not yet. Now, I am not arguing that survival is not important. Survival is obviously critical, but I would argue that it is necessary and not sufficient. I think that we need to revisit this framework from the lens of child development as Tarun Dua showed yesterday. You see some of her suggested indicators there. I will come back to the issue of indicator burden and proliferation which is obviously a core issue related to the line of argument I am making here in a moment.

As an aside, while we are talking about women and children’s health, I might say as a MMCH community we have actually shot ourselves in the foot with our focus on survival as our core message. This point was made to me most eloquently by Vishugy Kumar, who pointed out that the mothers he works within Srinagar do not want their children to just survive. They want them to thrive. Now, if I asked you or Kimber how you are doing today, and Kimber responded to me, “I am surviving,” that is such a de minimis answer. Yet, that is the bulwark of our communications messaging around women and children’s health.

I want you to think about your own children. How many of you here have children, raise your hand? Raise your hand if your primary goal for your child is that they just survive. I was talking last night with Gillian, and Gillian made the excellent point. She said that people are always telling me that we have got to focus on survival now. Let’s focus on child development when we get the survival job done. She said I am a mother. I have children. I am not going to wait until they are 5 to focus on their child development. I think she has got an excellent point there.

So I want to argue that to be more effective, we should actually pivot our communications in women and children’s health from pushing on the message of survival to actually pulling through a more aspirational goal and a more aspirational narrative and more aspirational language on thrival. That resonates with what people want.

Before I go on to discuss why I think we have failed, and you can see I am presenting this in the humblest and nicest spirit to try and generate discussion and move us forward, and what we should do to succeed, I want to remind you that I am in awe of the people in the room, and I am not using the F-word here, failure, in any way to diminish that.

Also, I just want to do a reality check. Is there anyone who wants to challenge the fundamental hypothesis here that on the one hand we have this incredibly compelling grand challenge? On the other hand, it is not reflected in the world’s score cards and the global frameworks for action. Does anyone think that is not true? You have to kind of accept that now before we go on. I would be very glad for any push-back. If I am wrong, it is fantastic.

Singer contends that “if we don’t pay attention to child development what this in effect means is we are killing entrepreneurs, creating criminals and promulgating sick and depressed populations.”

- What do think he means by this?

- In your view, is it an overstatement?

In the next clip, Singer highlights five reasons why "we haven’t translated this incredibly compelling global challenge (sic) into global action."

Singer - Part 2

Let’s try then to look at a bit of a root cause analysis of why we have failed, why we have this phenomenon of lost in translation and why we haven’t translated this incredibly compelling global challenging into concerted global action. I see five reasons. You may see others. I think offer the implications for action.

Firstly is the fragmentation of risks. We know that causes or risk factors in child development are extraordinarily complex and multiple. Everyone has their favorite risk factor, the nutrition people are fighting for nutrition. The vaccine people are fighting for vaccines. The early child education people are fighting for early child education.

On this slide, you see how our Saving Brains Program has actually been risk agnostic. That is the approach that I think we have to take. It doesn’t matter to us when we are supporting grants whether the causes or risks are biological or health-related, for example, are related to nutrition, related to infection, related to environmental toxins, whether they have to do with environment, enrichment and nurturing or whether they have to do with the terrible things that happen to children, abuse, neglect, or conflict. We are risk-factor agnostic.

It doesn’t matter if your brain is messed up due to biological factors like nutrition or infection or psychological factors like stimulation learning or protection factors. If you are in the real-world, it doesn’t matter if you are well-nourished if you are a child soldier or if your parents don’t sing to you or read to you or you aren’t able to play, you will be just as impaired. We need to take a holistic and integrated view of risks. I think that is the first reason why we haven’t really been able to get this translation done.

The second reason has to do with the disciplinary siloization of the outcomes. Some of the relevant outcomes are economic, like earnings, GDP. Some are social like violence and criminality. Some are health-related like NCDs and depression. The economists like the economics outcomes. The sociologists like the social outcomes. The health researchers and the health folks naturally like the health outcomes. Then what happens is by focusing on only one element of the burden, we minimize it. We need to see this problem holistically for the multifaceted huge burden that it poses.

The third issue I want to zero in on in terms of the cause of this loss of translation is the issue of metrics. I know you had a lot of discussion of it yesterday. I would characterize this as starvation in the midst of plenty. On the one hand, we don’t really have good metrics of child development early on when it really matters; let’s say in the first year of life or in the first two years of life. Therefore, we are left with this time lag with no prognostic indicators early on.

Let me just give a shout out to Gary Darmstadt, my friend and his colleagues at the Gates Foundation, who recently launched a grand challenge on identifying ways to measure early infant and fetal development, to try and really stimulate some creative thinking on these early indicators.

On the one hand we don’t have the early indicators. On the other hand, we have got plenty of metrics, especially later on from plenty of different organizations. Here, I just want to reference Joan who challenged us yesterday. She said we need the six metrics that fit on a dashboard that the policymaker can track in her country. These metrics need to be harmonized between health, education and protection and along the lifecycle. We need to become adept at measuring context alongside development outcomes when evaluating the impact of these interventions. I think that is exactly right.

My conclusion there is that we need to fix this metrics problem. Why do we need to do that? We need to do it in its own right. Metrics is also the gateway to accountability. That is how we drive global policy. If you try to influence one of these frameworks and they ask you how you want to measure it. Then you have six people from different organizations show and say here is our set of 17 measures and here is our set of 24 measures. Here is our set of 13 measures; I think you can just forget it.

The fourth reason we are not doing as well as we could be on translating this grand challenge into policy action is let’s call it politely political economy. When we say child development, many politically astute observers will hear big government and big spending. This automatically leads to a political divide that makes the challenge much more difficult to address.

We need to take another look at child development from the standpoint of a fiscally conservative approach. Sometimes it could be child development; here is your 75 billion. Sometimes we ought to take another look. In this regard, I think it is very significant that Secretary Clinton’s initiative, Too Small to Fail, is actually not about big spending. It is about simple things like the word gap in children and tweeting things parents can do to actually close the word gap and improve the development of their child.

I just want to remind you that it doesn’t cost billions of dollars in government spending for a father or mother to sing to their child, to respond to their child, to play with their child, or to set up a space for their child to play. I fully recognize the issue of invoking burden on care providers here. I do think that we need to break this pari passu linkage between child development and big government spending programs.

Building on this, I think we need to pay a lot more attention to innovative finance mechanisms in cases where you actually do need programs very significantly financed. That burden is going to be very hard for governments alone to bear. Corporations benefit greatly from workforce development and so on. Think about a mining company, a mining company goes into a country. Arguably on the balance sheet of a country, and I am thinking about that work on balance sheets of countries that was published in The Economist a couple of years ago.

It is taking money out in natural resources. It is trying to mitigate in the environmental asset category, but there is a human capital category where a mining company could really be replenishing. On balance, the effect on a country’s balance sheet is neutral or positive. There are very compelling arguments for corporations around workforce development in terms of this. That is why I think the type of innovative financing mechanisms, be it development impact bonds or other mechanisms, zeroing in on early child development are really something to look at.

The fifth reason I think that we are failing is the issue of how do we get to a truly global or universal challenge. If you listen to President Obama’s last State of the Union Speech, you will have heard his recounting of 50 years of the war on poverty and 75 billion dollars for child development. That narrative on the U.S. war on poverty and the effective interventions therein in early child development comes completely delinked from the global challenge of child development and the issues of international development and how countries can develop their human capital infrastructure to exit from poverty.

This is very ironic because the whole point of the post-2015 goals as opposed to the MDGs is that they ought to be universal goals. At the same time, it represents a huge opportunity to link the domestic problems that G8 and other high income countries have because every country has poor people in it with the broader problems of global poverty and how child development can be zeroed in on as a strategy there. The idea of universality and a truly global goal is something we should look at.

Challenge your recall of Singer’s five reasons we have “failed” with the matching exercise below:

Drag the reason for failure on the left to the appropriate explanation on the right.

Singer - Part 3

Where does this leave us with respect to our important work? I think it should leave us encouraged. I think what this forum is doing is exactly on the right track in terms of synthesizing the science, synthesizing the empirical evidence, synthesizing the economic data on child development. I would love to see, for example -– and this gets to the point that we have to think about how those messages are translated –- economic data on child development.

What is the total bill for neglecting this global challenge? We know that it is 200 million children, or there about. What is the total cost of inattention? That is the topic of the workshop. Maybe we will get the answer later. If you zoom in on a particular country, and you click on that country, what is the cost to GDP of that country for not paying attention to child development?

If you click on that country and you zero in on a particular risk factor and click on that, what is the cost in that country of neglecting that risk factor or a group of risk factors? That is the type of translational evidence that I think is going to be a compelling argument to finance ministers. That kind of evidence is only the start because you need evidence plus some of those advocacy elements to actually get the job done.

What I would love to see is let’s see these risks and outcomes holistically. Let’s develop a few easy to measure metrics as Joan was saying yesterday. Let’s try and sever the pari passu link between child development and big government spending. That is not to say that I don’t think the government should spend on this. I think they should, but I think that pari passu link is getting in our way. And let’s see this as a truly global challenge. Let’s not disconnect the U.S. war on poverty from the work that is being done in our global development agencies. Let’s see this as a truly global challenge. Let’s continue to build a coalition, a type of partnership that can tackle this. Fragmentation of our effort –- and I think this is a great service that this forum is doing –- kills hope for children.

At the tactical level, I am sure there are many things that we can do and think about in respect to these women and children’s health frameworks, in respect to the post-2015 accountability frameworks. What is our tactical play for UNGA for 2014 just as an example? I really wanted to tackle this problem at a more strategic level. I certainly don’t have the answers here, but I did want to highlight what I saw as a collective problem, which is ECD being lost in translation between the evidence base and the global frameworks for action.

I think –- and this is why I spoke in this way -– if we continue to ignore this failure, we will continue to get the same results. Let us each reflect soberly and suggest the way forward as you have these discussions today and at these workshops. Again, I think the forum provides a great opportunity to do just that. The issue should not be a picayune discussion about this little bit versus that little bit. It should be that as well. The job of the National Academies is that kind of evidence synthesis. While we are doing that, let’s at the same time always remember how these messages will be translated to policymakers.

Now, I do have cause for great hope. A thematic like reaching potential actually embraces all of these themes in a coherent manner. You can reach potential in employment. You can reach potential in governance, just as you can reach potential in women and children’s survival. If you frame this challenge that way, reaching potential, human promise, whatever the best message for that is, these indicators actually all fall in line and it valorizes the topic that we are all interested in, in child development and Saving Brains. Child development and Saving Brains should not be a series of footnotes on the world’s score card. It is just so important. Rather, it should be recognized as the grand challenge that it really is.

I hope I can still remain a friend of Zulfi, even though I came with a relatively critical lens, but I came with a critical lens talking about failure only in the best spirit to focus us on something early on where I think if we really pay attention to this issue of lost in translation, all of the efforts of this forum and all of the individual, awesome efforts of the people in the room can really be amplified much more greatly going forward.

Thank you very much for your attention. It is much appreciated.

In this final clip, Singer makes a plea that child development “not be a series of footnotes on the world’s score card.”

- What does that mean to you?

- What evidence would you look for in a community or country to assess the degree of commitment to early childhood development?

Pia Britto, UNICEF, prepared a report titled, Investment and Early Childhood Development (ECD) that reinforces Singer’s position that there is a huge gap between the potential benefits of ECD and the level of investment currently made by governments or the private sector.

1.1 The Scientific Rationale

The explosion of scientific research into early brain development in recent years expands our understanding of ECD. The old nature vs nurture debate has been put to rest as science has established that the expression of our genes is highly dependent on early environments and experiences. Genes are our inherited potential and bring a range of possibilities. Genes listen to the environment and respond to experiences. It is the interaction of genetics, environments and experiences that shapes human development.

The explosion of scientific research into early brain development in recent years expands our understanding of ECD. The old nature vs nurture debate has been put to rest as science has established that the expression of our genes is highly dependent on early environments and experiences. Genes are our inherited potential and bring a range of possibilities. Genes listen to the environment and respond to experiences. It is the interaction of genetics, environments and experiences that shapes human development.

With this knowledge comes responsibility. If the developmental trajectory of children is not driven by genetics alone, but by their interaction with environments and experiences, what does that suggest about parenting, public investment and society’s priorities? Health, education, nutrition, nurturing and social protection are proven to significantly contribute to the positive conditions that enable surviving and thriving.

View the interview below with Steven Lye, University of Toronto, as he outlines the scientific case for investing in ECD

Lye - Why Invest

You know I think, well we know, is that societies that do invest in children are more successful. That the period of early life is one in which the brain is developing. 85% of brain development is accomplished by 3 years of age, and that we have a, a window of opportunity, in which we can help these children reach their full potential, and therefore contribute to advancing their societies to be more successful. Unfortunately, currently, the investments that are made across the life course are occur least at the time when the brain can actually take advantage of these investments, and so there's this discrepancy between periods, sensitive periods in development when interventions can most beneficially impact the developing brain and the developing child, and when we actually put those investments into place, and I think one of the things of the forum is to try and understand what is science telling us about when investments should be made, and what types of investments should be made, and try and link that to new policies and programs that will try and allow policies to match with science.

Dr. Lye talks about the importance of linking investment decisions to science.

- Can you think of a program in your area that is premised on a solid scientific rationale?

Dr. Lye goes on to outline the three factors that contribute to healthy brain development.

Lye - Three Reasons

So I think we're at a very exciting time, we know so much about how the brain develops. We know that the brain essentially needs 3 things. It needs nutrition, because, and that's nutrition of the mother, particularly during pregnancy, because it's during pregnancy that the brain cells form in the child's brain, in fact, by the time birth occurs, that baby has 100 billion nerve cells in its brain. That's as many stars as there are in the universe, and as many brain cells as we'll have in our lives. So you need good nutrition, nutrition that produces energy because at the time of birth, most of the energy used by the body is used by the brain. You need good nutrition because you need a mix of calories and protein and lipids, a lot of the brain cells are formed of lipid, and so we need them. And then in addition to nutrition, you need stimulation, because once you form all of the brain cells, you have to connect them.

It's the connections between brain cells that form largely in the early first months and years of life that allow us to learn, that allow us to memory, and that provide the ability to develop social relationships. And these connections require stimulation. Early in life, the brain is like a sponge. the child is soaking up the entire environment around her, and stimulation from that environment helps form strong connections between the neurons that underlie our memory in learning ability. And then thirdly, the brain needs to be protected from abuse, neglect, and violence, because those circumstances result in stress within the individual and in high levels, chronic high levels, of stress hormones like cortisone that actually damage the formation of these connections and even damage the formation of the brain cells themselves. So a brain is a complex organ that underlies everything we do, and in order to build that brain, we need nutrition and stimulation and protection.

Science has now established that the environment has a critical impact on early brain development. Lye elaborates on this and the implications for children who are exposed to less than ideal environmental circumstances.

Lye - Adversity

So, we know that the child develops as a result of a genetic blueprint that broadly specifies how to make a baby. But, more importantly, science tells us that it's the environments around the child, even preconception, during pregnancy and during infancy, that are critically important in sort of modifying or modulating that genetic blueprint to set children on different trajectories that impact their lifelong health, their learning, and their social functioning. And we know that those environments are different for different children. Children that are exposed to less optimal or adverse environments start falling behind in their trajectories, and by the time they go to school, these children are falling further and further behind, leading to a lot of the inequities that we see around the world, in health outcomes, in learning outcomes, so we now know more about how these inequities and adversities impact the developing brain. They do so through increasing the levels of stress, which is negative to the development to the connections between nerve cells and our ability to learn and think. They do so by a process that we call epigenetics, which puts a chemical mark on that genetic blueprint, on the DNA, which alters where the genes are turned on or off, and impacts brain function and it does it also by impairing in a child's ability to take in stimulation.

So there are multiple aspects by which adversities influence the child's developing brain and different adversities have different impacts. I think the important thing to know is development is complex, and if we are to succeed in allowing all children everywhere to reach their full potential, we need to embrace that complexity and realize that interventions need to be smart.

Lye highlighted the complexity of early brain development and the potential impact of adversities. He reinforced that development is complex and “we need to embrace that complexity and realize that interventions need to be smart.”.

Michael Georgieff, University of Minnesota, also spoke at the Washington workshop and emphasized the importance of using science to determine best investments. . View the presentation below, paying particular attention to his position that there should be "biological plausibility to interventions."

Georgieff

Good morning everybody. It is an honour to be here. This is my responsibility I guess to kick this off. I do want to tell you a little bit about what my goals are in this first talk. I think my responsibility here is to convince you if you are not already convinced that there is a biological plausibility to these interventions that Zulfi so well characterized. We should not be applying things willy-nilly, but rather think about the biology that is behind brain development, the fact that behaviours that we are interested in emanate from the brain. The brain has a very, just like the growth curves that we are describing – has a very well described way of developing.

I would be remiss if I did not say that this talk is actually put together by several people. Sarah Cusick, Bruce McEwan, who helped with the stress section, and Ted Wachs, who helped author the psychological section.

I am going to divide the talk actually into two halves. The first half is what we are going to call rules of engagement. These are the rules that I think need to be applied in order to assess what brain development is doing and the impact of environmental factors, whether it is nutrition, whether it is stress, whether it is environmental enrichment on that developing brain. And the reason to do that is so that we are not essentially waving our hands, but instead know that there is a stimulus response rate. That if we do an intervention that there will be a change in the brain in particular areas and then one can expect changes in behaviour based on those changes in the brain. There is a pretty rich biology both in preclinical studies and now in emerging evidence in human studies to say that this is a real phenomenon.

And then in the second half of the talk, we will quickly go through each of these major areas: nutrition, stress, and environmental enrichment to see what the evidence is in terms of better outcomes.

If I leave you with nothing else, I would like you to realize that the positive or negative effects of any environmental stimulus or any environment effect on brain development is really based on two things. It was really captured by these very smart people here and that is that it is going to be based on the timing and the dose and duration. Those are two things. Think about dose and duration as an area under the curve. It is the magnitude of effect both in terms of severity and duration.

And environment in our context could mean nutrition. It could mean stress. It could mean nurturing events or some combination of the three. One of the challenges will be to ask the question whether interventions in any of these overlap the opportunities given from the other areas. I will explain that in a second.

The first thing is to disabuse you of the idea that the brain is an organ. It is actually multiple organs. To talk about the brain would be to talk about something like the thorax. There are many organs in the thorax, the heart, the lungs and so on. They are all interconnected, but they all have their separate entities as well. That is true for the brain as well. The brain is not a homogeneous organ. It is made up of many different areas, different cell types. These different regions have different developmental trajectories. Many of them start their development in fetal life, which has implications about maternal intervention. And many of them continue throughout adolescence and even in to early adulthood.

The vulnerability of a brain region to any environmental insult is going to be based on two things. The timing of the deficit or enrichment programs during the lifespan. We do not apply equal therapies throughout the pediatric lifespan. And the intersection between that and the brain’s region requirement, for example in nutrient or its vulnerability to stress or its receptivity to enrichment at that time. Again, that varies across the lifespan from fetal life where the placenta essentially filters very much of the external environment through adolescent life it seems where you are very exposed. The two really have to come together. I will give you a very palpable example.

You are not likely throughout your life – you are not as much at risk throughout your pediatric life equally at risk to be for iron deficiency. There are times when you are much more at risk for iron deficiency than other times based on growth, based on transport, all sorts of reasons.

Similarly, different brain regions have a higher or lower requirement for iron at different times in the lifespan. The vulnerability comes when you have high demand and you have lack of availability. We are going to try and identify some of those and again see how well these overlap.

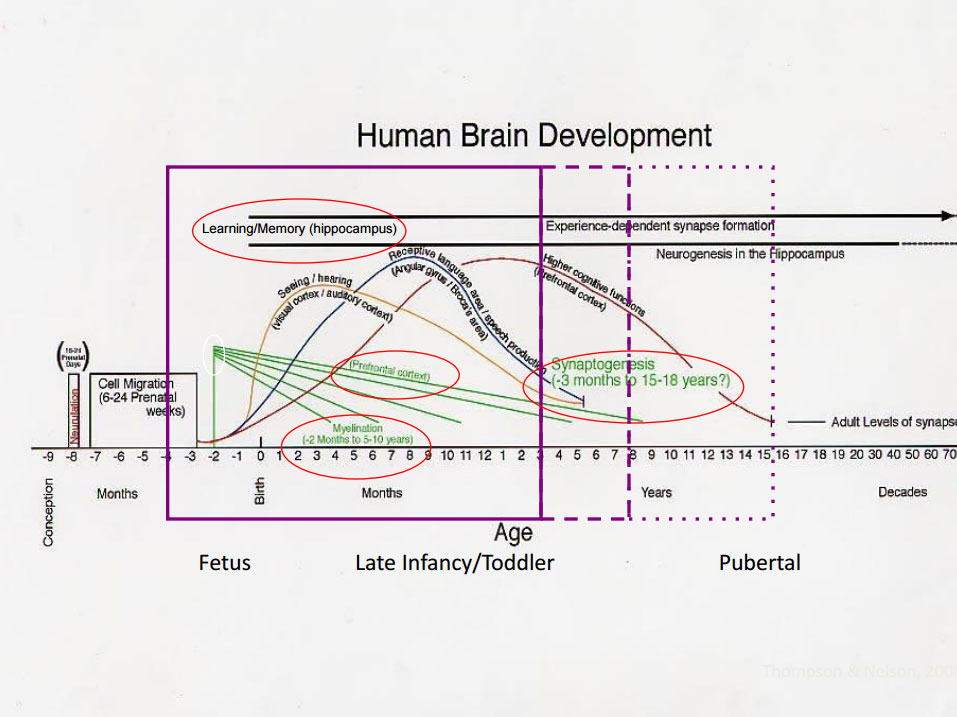

This is one of my favourite slides. If you want to capture all of human brain development in one slide, this is the one. This is from my friend Chuck Nelson. I am very thankful that he published this back in 2001. Many of us in the field use this slide. It looks a little complicated, but I want to impress a couple of things on you here. First of all, you will notice that the x-axis is very stretched here. Most of life actually occurs out here. This is where most of us are. You will notice that there is not a lot of brain development taking place out there. The fact of the matter is we do have experience-dependent plasticity. It is a good thing. That means we are going to learn something here today.

But if we start in fetal life here before birth at time zero, we see that myelination, so speed of processing in the brain, synaptic genesis, connecting up your brain, learning in memory, hippocampus are all well underway by the time the baby is born at term. It tells you a lot about maternal fetal dyad health.

The frontal cortex here already developing early in the early months. We do not think of babies as multi-tasking particularly. But in fact, that area of the brain is developing rapidly and will be vulnerable to either insults or receptive to interaction.

I have put a solid box around zero to three because of course that is what everybody thinks about. But you have noticed I have extended that with these more dotted boxes as we go out even in to the teenage years. That is to remind me to tell you not to forget that there are opportunities out here. The bottom line is it is better to have done it right in the first place, but there are opportunities because development continues not through just the teenage years, but presumably through the lifespan.

When we do large-scale studies particularly in humans, there are many outcomes. Behavioural changes are among them. We are trying to improve children’s behaviour largely writ. In the rules of engagement, these behavioural changes need to map onto the brain structures and circuits that are altered by environmental experience. That is, we cannot just say poor environment here at the beginning of life, bad outcome here. Gee, they must be connected. The question is how does that environment get under the skin? How does that affect the brain and what can we do to either enhance or interrupt a process? That is important because sometimes you will come to very different conclusions about what the intervention should be if you know what the biology is.

Some of the effects are transient of certain deficits, for example, certain nutrient deficits. They alter brain function while you are deficit. And others are much more long-term and that is an interesting problem in neuroscience. Is that because you built the brain wrong in the first place during that window of opportunity or is the brain dysregulated across the lifespan? Those are not mutually exclusive possibilities.

The bottom line again is that there should be a biological plausibility for our behavioural outcomes, our social outcomes and so on. There must be a reason why in the brain these things are happening.

We talk about vulnerability and plasticity during rapid brain development. The early brain, the child from fetal life through the first few years is very plastic. They are very recoverable brains, but they are also very vulnerable brains. I think the NIH probably stated it best that on the whole vulnerability outweighs plasticity. Another way of saying that is it is better to do it right in the first place than to try to get kids who are off trajectory to come back.

There is a tremendously interesting literature on the biological basis for true critical periods. We argue about critical versus sensitive periods. We would like to think that no window is ever closed, but in certain biologies indeed there are critical periods where beyond that time point nothing can be changed.

This basic biology is important because it may be possible in the future to reopen critical periods, to reestablish plasticity in the brain. That is a very exciting area right now.

Early neurodevelopment is important immediately and later for two reasons. One, in those early years what I showed you on that slide is primary systems are developing. These are the ones that support learning and memory, the ones that support speed of processing and the ones that support reward. They are being shaped and sculpted early on. They are important in turn for scaffolding for the next order of systems to come in to place. Your frontal lobe for which you do. The ones that really get you through school. Working memory, prioritization, attention, inhibition and those kinds of things. It is important both early to do it right and then to continue beyond that. I will show you some evidence of that.

The possibility that there are these differential sensitive periods – it is possible that these sensitive periods have different time points in development. For example, many of us think that the nutritional effects are early in brain development. That reduction of toxic stress is important throughout development. That environmental enrichment may have a little bit more effect later on. These need defining over time. I would not turn any of this in to policy at this point, but we need to see where the evidence lies for that.

The primary question is if our resources are limited, what times are the best times to intervene? Where will we get an integrated biological and psychosocial intervention?

Let me briefly run through each of the things that are important in a child’s early life. What I have listed here is nutrients that are particularly important for brain development early in life. Again, we are talking about fetal though three to five years of age. All nutrients are important for brain development. But there are certain ones that seem to have a particularly profound effect. They include protein and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, iron, zinc, iodine, copper. These should be familiar to you. They are the ones that we look at throughout the world and through many young populations. And here I have listed and you can find these on the website, the areas of the brain that are affected and the particularly high demand periods.

And there is some clinical data that go along to suggest that there are sensitive periods for nutrient supplementation. For example, a recent publication that growth velocity prior to a year, but not afterwards, predicts IQ at nine years of age that linear growth has a strong association with brain development. We use to think it was growth equals weight gain. It turns out linear growth may be a better surrogate for actual structural development of the brain.

Similarly, fetal supplementation of iron and folic acid appears to improve working memory and inhibitory control at seven to nine years of age, but later supplementation does not seem to have as much of an effect.

Bruce McEwan has spent most of his research life looking at stress and types of stress. Stress is not necessarily a bad thing. Stress actually sharpens your focus in many ways. A little bit of stress is probably good. Toxic stress is not and that is what he of course studies. This is exacerbated by chaos and abuse and neglect. It results in a very unhealthy brain structure.

I want to show you what the effect is of toxic stress, chronic inflammation and so on down to the hippocampus, the area that is really the seat of recognition memory. It truncates dendrites. It makes for smaller synapses. Over here, I have shown you exactly the same type of effect due to iron deficiency anemia. It turns out that the end result of either of these toxic environmental effects is to shrink your dendrites, make for smaller dendrites and less efficient behaviour.

In fact, one of the questions we need to be asking throughout this conference is what is the interaction between these various things? It turns out there is a two-way street between nutrients and stress. Stressed individuals do not absorb nutrients and traffic nutrients in the same way that a healthy non-stressed individual does. Similarly, malnutrition results in a poorer or more blunted stress response.

In terms of early enrichment, I think there are plenty of clinical studies that show that early environmental intervention results in better outcomes. I have listed some of them here. Six to 12 months is a sensitive period for promoting secure attachment. The early years of life are particularly salient for interventions to improve quality of parenting and at interventions during the early years in both high and low income countries have long-term cognitive and academic effects. But the point is you cannot stop there. There are plenty of studies to show that when you end the therapy, things regress back to the mean. Follow up and follow on therapies are important both to stabilize and improve what was done in the early years.

The process does not end at five years and that was why there was that final dotted line out there. Adolescence is an unexplored area in many ways. There is a lot of brain change going on there as well. It is a chance for catch up and it is a chance to solidify that scaffolding that we have done with our early interventions. We see that experienced dependent brain development in adolescents mediates lots of very high-end things that ultimately will decide economic and social status and improvement of society in general.

Conclusions. Early development is important. You cannot make it all back up just by intervening later. You want to scaffold the brain correctly in the first place. For some fundamental things like learning and memory and speed of processing then the neural scaffolding for the more higher end functions as they come along. These early events confer a lifetime of risk partly through epigenetic modification of genes. The early period is not the sole sensitive time, but it gets harder. It gets harder as you go along.

These follow up and follow on interventions are crucial. Integration across all of them are important because there is crosstalk between nutrition and stress, between stress and environmental enrichment. We need to think about how we channel those together to improve the brain’s development.

I will stop there and we will move on to our next talk. Thank you.

Georgioff utilizes a chart which he euphemistically suggests "capture(s) all of human development in one slide."

Click to expand in new tab

- What strikes you most about this chart?

- Can you think of examples of programs, interventions or public investments that reflect the information on the chart?

- Can you think of examples that are contrary to the chart?

1.2 The Economic Rationale

Investing in young children brings immediate and long-term benefits to individuals and societies in low-, middle- and high-income countries. The cost of inaction is staggering. Investing in early childhood is an essential ingredient for effective humanitarian aid.

Investing in young children brings immediate and long-term benefits to individuals and societies in low-, middle- and high-income countries. The cost of inaction is staggering. Investing in early childhood is an essential ingredient for effective humanitarian aid.

Read the following United Nations blog posting by Mary Young, Director, Center for Child Development, China Development Research Foundation.

- Young refers to ECD as a powerful equalizer. What do you think she means by this?

- If you were in the challenging position of influencing a significant investment in either employment opportunities for disadvantaged youth or early child development programing for their younger siblings, which would you select?

The economic argument for investment in early childhood is robust. So why is investment in ECD not universally accepted as a priority area for public investment? Listen to the following interview with Jody Heymann, University of California, Los Angeles as she outlines two misconceptions that may contribute to this pattern.

Heyman - Economic Investment

I think there are two things that mistakenly often keep countries from investing in young children. The first is the notion that it competes with other investments, that we have to take away money from something else to invest in early childhood, and while that may be true for a very brief time, the returns to investing in young children are so powerful in terms of better economic outcomes for their families, better economic outcomes as the children grow, better educational outcomes, reduced adverse outcomes that it more than pays for itself, this is totally affordable. The second is that we think it’s just easy to forget about young children. They’re not claiming policy makers’ attention, they’re not organizing in the streets and they seem so resilient and of course in many ways they are resilient, but the price of not investing in them is enormously high, and the return is extraordinary, so I think the question for all of us is ‘how can we motivate our own governments to make this investment that we know could have such a powerful impact on the lives of everyone – on the lives of the children themselves, on their lives as they become adults and on the success of all our societies.

Heyman asks the question, “how can we motivate our governments to make this investment that we know could have such a powerful impact on the lives of everyone?"

- Can you think of three ideas to motivate government to make significant investments in ECD?

In the interview below, Sara Watson from Ready Nation reminds us that the responsibility to invest in human capital and particularly the early years does not lie with government alone. She speaks about the importance of engaging the business community to invest early to strengthen the workforce and the economy.

Watson - Ready Nation

Ready Nation is a global business organization of 1400 executives and all of our members want to improve the economy and work force, and they believe that investing in children starting in the earliest ages is the best way to grow the economy and produce a strong workforce.

Business leaders can do a wide range of things to support young children. We talk about this in 6 categories of action that I'll describe briefly. At the most local level, they can donate money and volunteer as an expertise, a traditional corporate social responsibility role. Secondly, they can work through their employees, giving them family friendly practices, as well as educating them on the importance of early childhood. They can use their customer base as a way to educate more people about the importance of early childhood. Fourth, they can develop products, goods, and services that make money but also contribute to the social good. Fifth, they can use their platforms to speak out on the importance of early childhood through the media or other prominent venues, and then perhaps most importantly, we want them to use their clout and their reputation in their power to influence policy change so that we can increase public funding for early childhood investment from the local level, to the national, to the global levels.

- Are you aware of businesses or business leaders who have supported local initiatives or championed the cause of early childhood?

- What impact might this have on governments’ willingness to invest in the early years?

Watson goes on to elaborate on the importance of engaging a range of “powerful friends.”

Watson - Powerful Friends

Early childhood advocates have been in the trenches for decades, fighting for better recognition and more funding for early childhood, and they continue to be the experts on what the system should look like. But as a colleague of mine once said, "Powerless children need powerful friends." In order to get the dramatic increases in public funding that we want, we need powerful people to use their reputation and their clout to convince policy makers that this is in the best interest of their community, their state, their nation, whatever nation that is. So, we used business leaders not as a substitute for the advocacy of the early childhood community, but as a supplement to show that this investment helps everybody.

So when we say unexpected champions, we mean leaders, powerful people outside the early childhood field, who are willing to say that early childhood is an essential part of improving a country's wellbeing. These can include business leaders, not people in the childcare field, but business leaders from other companies. It can include police officials who are willing to say that early childhood is a wonderful way to reduce crime and violence. It can be athletes, celebrities, doctors, teachers of older children as well, all of these people can say even though we're not in the field of early childhood, we believe that this is an important investment. And those statements carry a lot of weight with policy makers, specifically because those people aren't from the early childhood world.

- Can you think of two prominent people in your community who could be “surprise” advocates for ECD investment?

- How might you persuade them to become champions?

In this last clip, Watson draws on international examples to highlight ways in which private sector companies can support their current and future workforces, through supporting effective early years initiatives.

Watson - Building Workforce

In many different countries, including low income countries, business leaders want to expand and they can't find enough well-trained employees to expand their businesses. We found this was the case in Uganda, where we worked with an organization called Private Sector Foundation Uganda, to spread this message to their business community that early childhood was a way to improve the ability of these businesses to have a workforce ultimately that could do the jobs that they have. So, the issues of being able to create a productive workforce are very widespread. It was also important for companies to be able to support their current workforce, and that's true in a wide variety of countries. Obviously the India Mobile Crèches are a wonderful example of companies participating in a childcare initiative that helps support employees on the job. So, I think companies at many different levels need a better workforce that's more highly trained. They want to be able to support the current workforce, they want people to have better health outcomes that will reduce cost and make them more productive adults, and those arguments apply across a wide variety of income levels.

The business leaders that we work with want the same type of happy play based, developmentally appropriate services that the early childhood community wants. We're not talking about making little children into widgets, or sitting them at desks, or talking about forcing them into careers at age 2. We're talking about business leaders saying that the developmentally appropriate services that have been shown to make children's lives better are a great investment for our nation, and we're willing to use our clout with policy makers to get the investments that we all want for young children.

In addition to building the scientific and economic rationale for ECD investment, many experts and advocates see ECD as a critical component in a strategic approach to tackling some of the world’s most complex issues and supporting long term global sustainable development.

1.3 The Social Rationale

The Forum on iYCG recognized that investing in young children is the ramp to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. A children’s rights framework is replacing a charitable framework and related focus on deficits.

The opening comments made at the November 2015 Prague workshop, provided an overview of the shifting focus of attention as a result of the establishment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Listen as Nives Milinovic, of the Step by Step Association, brings opening comments followed by Hiro Yoshikawa, New York University and Zulfiqar Bhutta, Aga Khan University and University of Toronto.

Milinovic & Yoshikawa: Sustainable Development Goals.

[Introduction Milinovic] DR. MILINOVIC: Thank you Sarah. Good morning ladies and gentlemen. I’m glad and honored to give the opening remarks on behalf of the International Step by Step Association. For the first time early childhood is on the global agenda, taking the issues of quality, equity, gender balance, nutrition, health, and qualified workforce. It was put on the global agenda by the Sustainable Development Goals, which were adopted by the UN a month ago. The targets are very important, as they indicated the world’s highest priorities for the future of our planet and for all children and families from all over the world. Also the targets provide a clear guidance on how much we still need to achieve in many countries, not only in the developing countries. Let me just mention the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe. I come from Croatia, one of the countries on the refuge road, and we are witnessing daily the suffering of thousands of children and their families who have to sleep on the frozen ground, hungry, thirsty, sick, and facing an uncertain future. And this is all happening on the ground of Europe, one of the most developed and richest parts of the globe. The UN target, an inspiration to ISSA’s work, and as a network we are ready to share and facilitate learning between countries and to contribute to advocacy movements to address the most critical issues, especially related to quality and equity in early childhood. We believe that there is a tremendous need to bridge research, policy, finance, and practice, while keeping in mind that investment in people is the hardest but the longest investment. We believe that this workshop will be an inspiring sharing and learning experience, and will bring forward discussions that are so much needed when referring to the most excluded groups of children. Let me end with the motto of ISSA’s initiative for Roma children. The initiative is the Romani Early Years Network, and the motto is no more lost generations. Thank you.

[Introduction Yoshikawa] DR. YOSHIKAWA: It’s a pleasure as a new member of the Advisory Boards of the Open Society Foundation’s Early Childhood Initiative to welcome you to the conference, as well as a member of this forum on investing in young children globally. And I would like to accentuate the issues of exclusion that are currently at crisis proportions worldwide, with over 600,000 children who have made ocean crossings across the Mediterranean to Europe in 2015, over 500,000 of them have applied for asylee status.

So this is the latest in a long set of marginalized groups, including the Roma, including the disabled or those with different abilities than mainstream children, those of different ethnic and home language groups who are often excluded, not only in low and middle income countries but also in rich countries around the world from systems of early childhood development, primary education, early health, and nutrition services. So this is an extremely important issue. It has been one that our forum has addressed in its first several meetings, but not in such a concentrated way as it will in these next few days.

The Open Society Foundations will also be releasing an important report on the situation of Roma children in the Czech Republic this week. So I very much look forward to these data, this information which will be relevant to all of us no matter what country we’re coming from to bring back to our nations, to our programs and policies to fulfill the universality of the Sustainable Development Goals.

As any of you know the language of the SDGs is much more universal in character than that of the Millennium Development Goals. So while retaining goals of extreme poverty reduction, really the goals are meant to be relevant to all of us, because they are about all boys and girls growing up in situations of access to quality early childhood development programs and policies. Thank you very much.

In the following clip, Bhutta elaborates on the significance of the shift from the Millennium Development Goals to the SDGs. As you watch, take note of the differences in the two approaches.

Bhutta - SDGs

So as you know the sustainable development goals which have now replaced the millennium goals, the MDGs, are very different in that health is just one part of it. But a lot of the goals, those that relate to the environment, poverty, living conditions, nutrition, gender sensitivity, adolescent health, climate change; they’re interlinked. And they’re linked to each other because they are fundamental determinants of health and outcomes. So one thing that has happened with the background discussion and planning for the sustainable development goals is that we have very effectively said, we’ve made good progress as a global community in reducing mortality. It’s now time to also bring into the discussion the whole issue of quality of outcomes, morbidity and recognizing that to save a life, but not to give that life proper opportunities for growth, development and optimal outcomes is actually not a global purpose. So as a global community, we are now really very focused on quotes, un-quotes, allowing all children, families everywhere the opportunity to develop to their best potential. And this means that, fundamentally, we are not looking at band aid solutions of you know, providing interventions to save a life here alone. That’s important in its own right but not sufficient. But we are looking at the entire continuum of child health, school health, adolescent health, maternal health, early new born, infancy, children as a continuum in terms of seeing what are the risks, the barriers, the pit falls that need to be addressed and how can they be done both within health and outside of health.

- What are some of the significant differences between the goals and approaches of the MDGs and the SDGs?

- How might this relate to ECD?

Listen as Bhutta ties together the social and economic rationales for investing in young children.

Bhutta - Human Capital

I think leaving children and families who are at the margins of society who will fall through the cracks and are ignored is overall hugely detrimental to any given society, be that high income, middle income or low income countries. Because firstly, you are unable to achieve what you need to achieve as a society on the whole. Secondly, you are also exposed to a whole broad swath of your population that’s completely out of the development domain. I mean can you imagine a country where a large proportion of its youth are disaffected, unemployed or unemployable, are not in optimal health, are exposed to all kinds of violent crime, drug abuse etc? I mean the cost, the net cost of that to a society is huge. So the argument that we need to invest in our children is a very pervasive argument which, on the one hand, it’s a rights argument because every child has a right to health, you know, development to the same extent as the other. It is also a common sense human development argument. No nation in the world can ever climb the ladder of progress without investing in its children, without investing in its families. So at the end of the day, ministers of finance, planning commissions, politicians, prime ministers, presidents have got to recognize that this is just as important as building roads, bridges and dams. Investing in the human capital of a country is the difference between making the leap into the twenty first century or staying behind and forever being restricted in terms of what you can offer as living standards to your communities and societies.

As can be seen by the presentations above, it is possible to view ECD investment as a key strategic approach to achieving the overall SDG goals. ECD is also specifically included in SDG 4 – the quality education goal – which sets the following target: By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and preprimary education so that they are ready for primary education.

Larry Aber, New York Univeristy, discusses Sustainable Goal 4.

Aber - Sustainable Development Goals

The forum began before the sustainable development goals were passed and it’s coming to a close after the sustainable development goals have passed. The sustainable development goal four is the education goal, for the first, during the millennium development goal period from 2000 to 2015 the chief education goal globally was to create universal access for kids in primary school. And so access has been job number one for the global community, but what we’ve discovered is it’s relatively easy to get kids into school and extremely hard to help them learn during school, and so there’s a shift in emphasis from the millennium development goals in education to the sustainable development goals in education, where the goal now is quality of learning for, quality education and learning for all. And so that’s meant to signal that being in a school isn’t enough, it has to be of sufficient quality for you to learn and it has to be learning that is creating equity for everybody. So quality, learning and equity are the three new policy signals that all the nations of the world have endorsed through the sustainable development goals and I believe that this forum will have a positive legacy going forward to the extent that its provided a step up onto the horse of the sustainable development goals. The sustainable development goals will become to monitoring and accountability force in the world to improve education over the next fifteen years and what’s great is a number of the members of this forum championed an early childhood target under education, so target 4.2 includes quality early childhood and child development and that wasn’t on the millennium development goals. The global community said early childhood is one of our sustainable development goals and that’s a very exciting thing.

Aber states that simply providing access to school is no longer sufficient. "It has to be of sufficient quality for you to learn and it has to be learning that is creating equity."

- How would you apply this concept to the creation of ECD programs?

Summary

The scientific, economic and social rationales are compelling: ECD sets the trajectories for individuals and for society. ECD programs and resources can be game changers now and in the future.

- Science continues to produce strong evidence that reinforces the lifelong impact of early experiences.

- Investing in ECD is an investment in individuals and societal well-being and prosperity.

- ECD programs and resources remove barriers to opportunities and reduce inequity and are an integral element of a sustainable development agenda.

Read the following article, in which the Director General of the World Health Organization, the Executive Director of the United Nations Children’s Fund and the Vice President of Human Development at the World Bank Group integrate the scientific, economic and social rationale for investing in ECD. Note the commitment their organizations have collectively made to ECD.

Test your understanding with this review. Click on the arrow to the bottom right to begin.

Test your understanding with this review. Click on the arrow to the bottom right to begin.

Read the statement below and fill in the missing words in your mind. Then click on the blank spaces to reveal the proper words.

It is the interaction of genetics, environments, and experiences that shape child development.

Think about three things the developing brain needs. Then click the blank spaces below to confirm your answers.

1) Nutrition 2) Stimulation 3) Protection from stress/abuse

Read the statement below and fill in the missing words in your mind. Then click on the blank spaces to reveal the proper words.

The Sustainable Development Goals are premised on the concepts of universality, integration, and transformation.